HELIOS

It all started with a little cinematic experiment I’ve conducted in order to test a vintage Soviet lens Helios-44M-4 2/58 mm next to a very popular modern Sigma 18-35 ART lens with my Blackmagic camera. Actually it was not only about technology. It was also a visceral experience of re-discovering emotions and memories buried under the decades of life experience. It reminded me that photography and cinema as artforms are not about technology, but about evoking emotions and memories. Since our memories are just emotions preserved in time. Technology and art help us to create and recreate this visceral experience, something that we feel deep in our guts but often don’t dare to express and suppress for years. The ancient Greeks, who invented drama and theater, called this process – catharsis – which can be translated as cleansing and was associated with the effect drama produced on the soul or psyche of the audience.

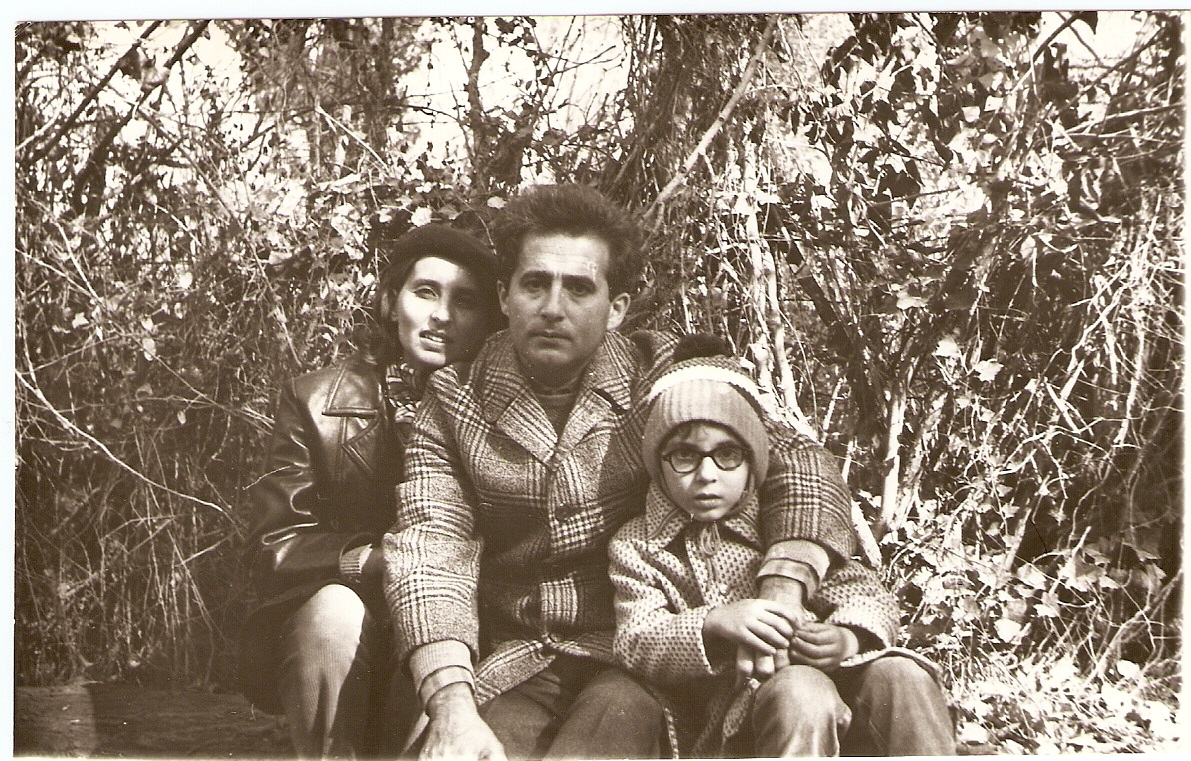

My Helios lens brought about this cathartic experience. It was a part of our family history, the lens my Dad used back in the 80’s in the days of the USSR together with his Zenit photo camera.

As a child I helped Dad with developing film negatives and printing photos. We would turn the bathroom of our apartment into a makeshift photo lab suitable for darkroom printing. I was always waiting in eager anticipation to be immersed into this mystical atmosphere, thankful that Dad had initiated me into this obscure world, where only two of us could co-exist. My younger brother and mom were never allowed to participate in this secret rite, to a great frustration of my younger brother, who would wait behind the closed door of the ‘photo-temple’, snivelling and listening to what we were doing in there.

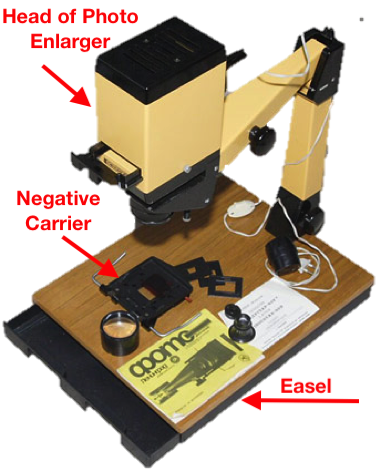

I would watch closely how father precisely arranged strips of a black-and-white film negative into the carrier of a photo enlarger – a huge and extremely expensive piece of equipment called “Leningrad-6”, Dad used to print photo’s with. From the agitated discussions of my parents I could conclude that this ‘damned apparatus’ (as my mom called it) together with his Zenit photo camera and all accessories had cost a fortune. For all that money one could buy a little Soviet car. Mom had strong reservations about this investment, to put it mildly. Dad said he would turn his passion into profit by moonlighting as event photographer or a photo journalist. You had to invest first before making money. I totally agreed with Dad, we didn’t really need that funny car, producing so much noise and fumes.

As the lights went out and we would get submersed in a red light of safetylighs, the magic would commence. I remember that wondrous moment, when I saw for the first time in my life how faces of strangers started to appear slowly on the exposed photo paper, immersed into a tray with developer. It had something to do with microscopic silver particles on the photo paper, all that my child’s brain could grasp from the explanation of my dad. I saw this modern alchemical process unfolding right in front of me. I could literally see the magic, smell it, hold it in my hands. Silver was turning the invisible world into visible. As if we were catching a ghost of someone, someone who died a long time ago, but we made him resurrect. At least his image, the trace he left in time. All that silver on the photo paper, all that caustic chemical crap – developing and fixing agents, reminded me of the ‘water of life’ and ‘water of death’ from dark fairy tales by the Brothers Grimm and Russian folk tales. Just as my dad I came under a magical spell of this process. For me it was worth more than gold.

This process was similar to cooking, but instead of food you cooked the life itself, you were preserving the raw reality, you were catching the time, you were materializing the evanescent memories. The trick was not to overcook it, otherwise the photo would become too dark, due to the reaction of light-sensitive silver salts on a photo paper to the solution of photographic developer in a tray. You had not to undercook it either. You had to let the silver release the latent image it contained, like a seed containing life in it. You give it too much water it will rot, without water it will die. The secret formula of cooking the raw reality seemed simple, but demanded precision, dedication and practice. Just as anything in our life, this process was very much about having the right ingredients and about the right timing, the right action-reaction, turning negative into positive. It was a craft, a science, an art, and magic, all at the same time.

I remember how I helped to rinse the freshly-printed photos in the bathtub filled with water, looking at the floating faces of strangers. I made them swim like fish. Then we used to hang the photo’s to dry on a clothing line in the kitchen, having dinner in the company of strangers staring at us from the portraits my Dad made.

Those images were etched forever on the walls of my memory hall, and I could say determined me as I am today, formed my whole life. Back then my child’s brain resembled a photo paper absorbing all the images into my head and projecting those images into my future. This unforgettable experience helped to expose some latent aspects of my personality, my human silver salt, my spirit, and materialized my passion for creating images.

Ten years ago my Dad gave me his old Zenit with the Helios lens as a present as I graduated from the Film Academy in Amsterdam. All these years the Zenit and the Helios lens were gathering dust, being nothing but a souvenir from the past. Reminding me of the sad fact that the relationship between me and my Dad was deteriorating with time, as the memories of the good things that we had experienced together were slowly fading away in the bitter darkness. Like photo chemicals we were drifting apart and falling in pieces, not being able to retain with time the original image, the ideal of being a loving dad and son.

REDISCOVERY

Well, there were moments when I even thought of getting rid of that Dad’s present…no need to collect those useless pieces of past, I thought. Though I didn’t dare to give it away, nor to throw it away…I’m a collector type of person. Happily. Recently I’ve re-discovered the beauty of a Helios lens both in combination with my Sony mirrorless photo(hybrid) A6500 camera and the little cinematic gem – the Blackmagic pocket cinema camera 4K.

I was literally blown away by Helios – my expensive modern Sony Zeiss

lens was boringly perfect, if not to say perfectly boring next to the

Helios.

What a treasure I received from my Dad!

The next thing I decided to test it with my BMPCC4K side by side with my Sigma 18-35mm ART lens.

Needless to say that this experiment had a big sentimental value for me. So, in no case I try to be objective, these are all my subjective findings, which I’m sharing here. I love vintage lenses, and I shot several short films with super 16 mm film with vintage camera’s and lenses as a film student, some ten years ago when Blackmagic cameras even didn’t exist. You can watch my award-winning graduation film Bingo here, which I partially shot with vintage Soviet 16mm camera Kinor: https://vimeo.com/37655407

In the process of my little filmic experiment I decided to edit my Helios/Sigma/BMPCC4K footage and to make a short film by developing some sort of narrative montage structure without having and actual story (or plot), and to see how each lens with its own characteristics can help me evoke a certain feeling and a cinematic mood. Eventually this process resulted in a short film, which I titled Vertigo Sun. You can see the first version of it here: https://vimeo.com/375901297

The footage is color-corrected – very superficially – since I shot it in raw (BRAW 12:1 and some shots 3:1, where a lot of dynamic range was required). I deliberately did not grade it, didn’t apply any LUTs, to show the differences between the two lenses. Then I decided to experiment further and to apply secondary color-correction and color-grade the footage. I tried to create a film look from the scratch, without using any LUTs. For that purpose I re-cut the footage, added several shots, and used other soundtrack. You can see part 2 here: https://vimeo.com/382099563

To tell the truth, I had a hard time of matching the footage shot

with two lenses – the vintage Helios is the total opposite of the modern

Sigma lens. It is soft, warm, grainy. It tends to produce more chroma

noise. It has a very beautiful bokeh, which looks almost like

anamorphic.

Strictly speaking this bokeh is an artifact, an imperfection of the

lens. However I embrace these imperfections, since they give the lens a

pronounced distinctive character, which can be used for artistic

purposes.

Unlike the vintage Helios, the modern Sigma is sharp, relatively clean, if not sterile, producing almost metallic cold, video-like look. It lacks a character Helios has. Considering the fact that this lens is very popular among the young filmmakers, and by some considered to be even legendary, I really didn’t like it, especially seeing the images it produced side by side with the vintage Helios lens. Perhaps it is good for some type of work – like a TV documentary or event videography. I don’t think that sharpness of the lens is the most important quality, when it comes to artistic, fiction/narrative work. Unless you make a horror or a sci-fi movie, where a sharp lens can enhance the feeling of anxiety. Besides a sharp hi-res footage is more suitable for CGI.

In my case I tried to use the sterile, metallic look of the Sigma

lens in order to accentuate a feeling of uneasiness, to create some

tension. During the second and the third pass of the grading, I managed

to subdue these inherent qualities of the lens, at least I tried to make

them less noticeable next to the Helios-shots, so that they wouldn’t stand out like a sore thumb.

I discovered a paradoxical principle – a flawed imperfect lens can make your footage look more naturalistic, more unpredictable and interesting like life itself, just thanks to its imperfections. While a ‘perfect’ lens makes a world look ‘perfectly’ boring. Should not we also apply this principle to our lives and embrace the imperfections – both our own, and those of others – instead of being judgemental, neurotic and lonely? Would not the world be so unbearably boring, pragmatic and sterile, if we all would become perfect ‘robots’?

Cinema is about finding light in the darkness, discovering the beauty

of existence with all its imperfections. Our imperfections is what

makes us unique as opposed to ‘perfect’

robots. The human DNA is identical among the human species, but what

makes each DNA unique? Errors in the DNA chain. Each chain has its own

unique errors, mutations, imperfections. Each DNA is damaged in its own

unique way.

As to my Dad and a me, I hope one day we’ll restore our relationship and finally embrace our own imperfections. I hope. I know it won’t be easy since we share the same DNA with the same imperfections.

Leiden

10-01-2020

Please consider reading the second part of my essay The Beauty of Imperfection – Part 2.