WHY ROGER DEAKINS HATES FLARES

Please consider reading the first part of my essay The Beauty of Imperfection – Part 1, which I published on my blog on January 9 2020

Image above: Roger Deakins – courtesy YouTube ARRI Channel

While grading my short film Vertigo Sun, which I shot with a vintage Helios lens, I watched a branded interview on youtube with Roger Deakins talking about the new ARRI Alexa MINI LF camera along with the new line of ARRI LF Signature Prime lenses, which Mr Deakins recently used on 1917, a new film by Sam Mendes. In that interview Mr Deakins says that he doesn’t like shooting with vintage lenses. To quote him:

”I am not somebody who will go to old lenses, because I like the patina of an old lens, something I don’t understand myself. I want the sharpest, the cleanest… I wanna lens that shows the world, or records the world as I see it. Which is, you know…I’ve got pretty good eyesight. It’s pretty sharp.”

He continues:

“I like to shoot with natural light sources. I like to shoot with practicals. And often, I’m shooting at something that is very bright […], so I want something that flares as little as possible. I cannot stand flares. “

Hearing that made my heart sink.

ROGER DEAKINS CANNOT STAND FLARES!!!

Mr Deakins went on with rubbing salt into my fresh wound:

“I find any artifact that is on the surface of the image a distraction for me. The audience or I am then aware that I am looking at something that is being recorded with a camera. Yes, I kind of shy away from that.”

A bit earlier in the interview Deakins mentions that he likes another ‘artifact’ – the noise…when he praises the image quality of the new Arri Alexa mini LF camera especially at shooting with high ISO values. He says:

“If you shoot 1600 or 3200, I know you could always underexpose.[…] it is remarkable, the image quality. Yeah, you get a certain amount of noise at 3200. …It’s a minimal amount of noise. I could quite imagine myself shooting the whole thing at that setting, to have that little bit of noise. It is a consistent nice texture. On a certain film that would be probably quite a good thing to have.”

Graininess gives a ‘consistent nice texture’, he concludes.

Initially I found these words self-contradicting, since Mr Deakins indirectly admitted that you can and should deliberately degrade the image you get from this super camera and the new super sharp lenses, in other words create an artifact – a noise pattern resembling the iconic film grain. What is also interesting about Mr Deakins approach to the cinematic image is that Mr Deakins received his international acclaim by experimenting with the form, with the film look, they way he chemically processed the film. He is the biggest formalist and experimenter out there, at least he was when he was young.

Deakins was the first European DP who introduced in the 80’s in the West a revolutionary Japanese bleach bypass technique of film processing, producing a characteristic washed-out grainy bleak look, the look which gained a wide-spread popularity in the 90’s after Fincher’s Seven (1995, DP’ed by Iranian-French cinematographer -Darius Khondji) and Spielberg’s Saving Private Ryan (1998, DP’ed by the Pole – Janusz Kaminski).

So yes, Mr Deakins always loved a grainy film image, and was deliberately pushing the graininess of the film by the chemical processing. In short, Mr Deakins is known for his bold approaches, when it comes to the film looks. He is in fact can be seen as a film-look guru.

He was also responsible for achieving the unforgettable (if not to say radical) sepia-tinted look of the Coens’ O Brother, Where Art Thou? (2000) by desaturating the lush greens and turning them into a burnt yellow digitally (using a digital intermediate – a hybrid analogue-digital process), after the initial attempts to achieve it via chemical processing in a film lab – including film bipack and bleach bypass techniques – had failed. In fact the film was the first film ever that was digitally color-corrected and graded.

However Mr Deakins remains remarkably conservative and consistent, when it comes to lenses, preferring a clean and sharp image of the modern lens to a soft ‘dirty’ image of the vintage one. He’s definitely not a sentimental type lens-wise. For mr Deakins a lens should not have any distinct character of its own, it should only serve as an optical tool, a precise interpreter or a portal (pass-through) between the objective reality and the cinematic realm; and it’s main objective is to create as less distortion as possible. No poetics whatsoever can be assigned to a mere distortion of the reality. Deakins totally ignores the creative virtue of the lens, since the optical ‘translation’ of the objective reality into the cinematic realm always per-supposes re-creation of the objective world. No machine, no cinematic tool, no lens is so perfect as to be able to merely copy the reality as truthfully as possible. Besides it’s not the point, we don’t go to movie theaters in order to merely see a copy of the world, since for us cinema is an escape portal to the dream world, we willingly leave our disbelief at the threshold of the dream temple, we all willingly ‘believe’ in the ‘truthful lie’ of cinema as artform. Cinema is not only about imitating life. To paraphrase Oscar Wild, life can also imitate cinema. Cinema can be contemplative, reflexive and creative – all at the same time,

as well as being able to predict the future or at least warn about the impeding catastrophes, e.g. the danger of AI or the prospects of total annihilation of life on earth, unless we wake up from our daytime slumber. So yes, it’s not only about escapism and propaganda, it is also about connecting peoples minds, hearts and souls.

Perhaps Deakins vision or ‘lens philosophy’ is formed by his background as documentary cinematographer long before his breakthrough in Cinema Valhalla of the world. In fact he applies a documentary like approach to the fiction. He thinks that camera just needs to simply register, the DP should not show off or flex his macho cinematic muscle – just be quiet, keep low-profile and register the flow of the cinematic life, a kind of oriental approach to cinema, similar to the contemplative reflexive style of a Japanese film director Ozu, who was the first to set his camera on the floor in order to follow his characters more closely. Less is more. Oriental paradox logic only a few Europeans can grasp. That is why Mr Deakins prefers operating the camera himself, favoring a one camera intimate approach. And this philosophy is also expressed by the choice of his film projects, as he mentions himself, he prefers small character-driven movies in stead of epic plot-driven productions.

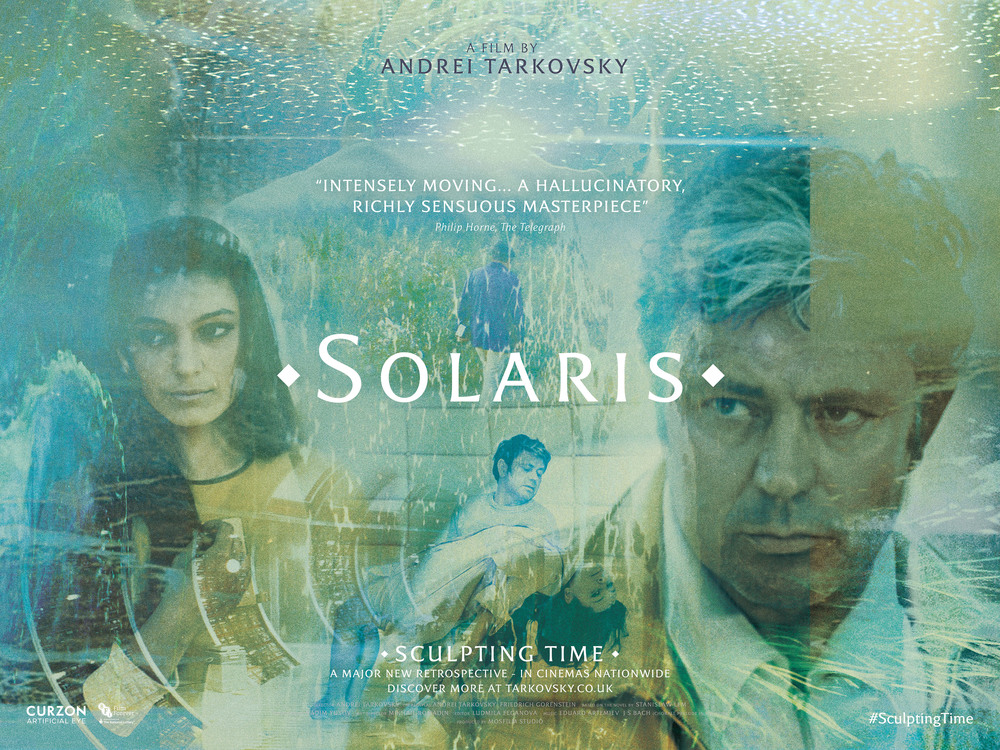

In his interview about his approach to the Blade Runner 2049, Mr Deakins said that if any shot stands out due to its beauty, it’s his failure as the DP, since his job is to orchestrate the film as an integral piece, not a collection of beautiful or ugly shots. We see here the same paradox logic. Don’t gild the lily. The art can easily turn to kitsch. In the same interview Mr Deakins mentions his source of inspiration – Solaris directed by the influential Russian (Soviet) director Andrei Tarkovsky, for which he received the Grand Jury Prize at Cannes in 1972 (DP’ed by the legendary Vadim Yusov ).

Perhaps this is the reason why Mr Deakins prefers shooting with Arri Master Primes, and always used primes. He asserts:

“…started off with Zeiss Distagons, the Planars, Cooke’s for years, Cooke S4’s, then went to Master primes”

Hence preferring spherical lenses to anamorphic. Apparently the ‘artifacts’ of the anamorphic lens – the horizontal magenta flare and its oval bokeh – which became the iconic feature of epic larger than life plot-driven Hollywood productions – mean nothing to Mr Deakins.

As he admits:

‘I have a perfect eyesight. I like to see the world sharp.’

Despite his respectable age he wears no glasses.

‘The man depicts the world as he sees it,” I thought, and took off my eyeglasses as I was writing this essay. And cleaned the lenses of my glasses with optical wipes, which had a nasty chemical smell.

So even Blade Runner 2049 (2017, dir. Denis Villeneuve) was not spared. Mr Deakins shot it – guess in three goes, yes with Zeiss Master Primes, which gave the film the metallic cold look, which is in fact (like it or not) very good for the apocalyptic story, the atmosphere, the mood and the emotional experience the movie tries to evoke and to portray.The lens choice is interesting since the original Blade Runner from 1982 was shot with Panavision Anamorphic C series primes by the American DP – Jordan Cronenweth. Riddley Scott, who was the director of the original but also the executive producer of the Blade Runner 2049, loves anamorphic lenses by the way. Watch this interview:

However David Fincher is also from the anti-anamorphic camp. To shoot through anamorphic lenses is a stupid idea according to David Fincher:

“I mean it’s a widely stupid idea, ‘cuz you’re just shooting through something that’s warping and distorting a picture.”

watch this interview: David Fincher on anamorphic vs digital anamorphic extract

However Fincher’s cult flick The Fight Club (1999) was shot with anamorphic Panavision Primo lenses by Jeff Croenenweth, by the way the son of Jordan Cronenweth, who DP’ed the original Blade Runner also with anamorphic lenses. Like father, like son.

Fincher’s background is TV commercials and big budget music video’s, Ridley Scott also comes from the advertising. Their approach to cinema is totally different than that of Deakins. However they’re are both masters of cinematic storytelling and know how to create very strong images, that can appeal to the masses. However I think that Ridley Scott has more artistic inclinations, not because of his love of the anamorphic lenses. Let’s not forget that before his Blade Runner became a cult flick and film classic, the film had flopped miserably in the box office. Apparently Sir Ridley Scott has a more risk-taking and experimenting nature. You need to be not only extremely talented, but also madly audacious to be able to step off the beaten track.

The advent of the digital intermediate (the hybrid analogue digital process), which was a transition from the film to the digital cinema, brought many possibilities but also a new aesthetics – what I call ‘photoshop approach to cinema’, ushering the era of CGI and digital image processing.

This photoshop approach tends to degenerate into ‘gilding the lily’, since it is very difficult not to be seduced by the borderless possibilities of image manipulation. This possibilities are often misused due to the widely accepted notion that ‘you can catch more flies with honey’, which results in feeding the masses with visual mind-numbing high-sugar diet.

As a result all wrinkles, pimples, all imperfections, all signs of life are getting ‘photoshopped’, so that the face of a young beautiful model or actress will be totally ‘perfect’ or ‘sellable’. Unfortunately this approach has become a commonplace in what is called ‘film industry’. I think it has to do with the fact that many film directors and DP’s have the background in commercials. So they brought this aesthetics of ‘glossiness’ and ‘fake perfection’ of ‘gilding the lily’ with them.

Well, wait a second, some might think, is all cinema and ‘film-making’ nothing but ‘faking the reality’, making gorgeous eye-pleasing images, in short making the reality more beautiful than it is? And is art not supposed to sooth us, to offer us a temporal relief, to help us heal our broken souls, to accept the cold facts of life? And isn’t the embellishment of life and crude reality by means of art something that we inherited from the ancient people?

Well, yes and no, I’m not against any form of entertainment, I’m against the one-dimensional approach to cinema. The visual diet must be rich in various nutrients, not only mental ‘sugar’. Remember, less is more, instead of the more, the better. Cinema is the art of not showing, when you show and explain everything it is not cinema, it is pornography.

However there’s some new tendency in cinema aesthetics – a nostalgic longing for the depth and texture of film as medium and at the same time adding an edge, grit to an image making it less glossy, less slick. Filmmakers tend to deliberately degrade the overly sharp crispy digital image produced by the modern hi-res sensors and lenses – by shooting with higher ISO values and using the native grain (video noise as Mr Deakins suggested in case of Arri Alexa Mini LF), or by using the softening filters that will degrade the sharp modern lens, and finally by adding artificial grain in the post-production and other artifices. The so-called ‘controlled imperfection’.

This physical degradation of the image goes hand in hand with the aesthetics of raw realism – the subject matter shifting towards the marginal figures and anti-hero’s – inspired by the Italian neorealism of the post war period, the French Nouvelle Vague, cinéma vérité, and in modern culture by the subversive photography and cinematography of Larry Clark in his harsh portrayal of American teenagers. This anti-aesthetics formed an antipode to the mainstream ‘sugar’ aesthetics and inspired such filmmakers such as Gus Van Sant and Martin Scorsese. In the meantime the subculture became a part of the pop culture as the film industry embraced this dark vision of life of the anti-hero.

As to deliberately degradation of the image in-camera and in the post,

My little experiment showed me that it is more aesthetically interesting and efficient to use vintage lenses instead of the modern ones and then ‘fixing it in the post’. Sorry, mr Deakins.

More and more filmmakers opt for vintage lenses with their imperfections, which help to ‘breakdown the digital image’ to quote Ben Davis DP of the Oscar Nominated Three Billboards Outside Edding, Missouri (2018, dir by Martin McDonaugh) who used Panavision Anamorphic Lenses with Arri Alexa XT Plus.

You can read the entire interview at British Cinematographer.

Or to use both old lenses and shooting with lower resolution (in 2k) as Sam Levy who DP’ed another Oscar nominated feature Lady Bird (2018, dir Greta Gerwin)

You can read the entire interview with Sam Levy and Greta Gerwig at IndieWire.

And of course the top-notch directors prefer simply film to digital image – Spielberg The Post (2018, DP Januzsc Kaminski, Panavision Panaflex Millenium XL2, Panavision Primo lenses), Chris Nolan Dunkirk (2018, Dutch DP Hoyte van Hoytema, IMAX, Panavision Panaflex Studio 65 camera, Panavision Sphero 65 lenses. And of course last but not the least – Tarantino Once Upon a Time in Hollywood (2019, DP Robert Richardson, Panavision Panaflex Millenium XL2, Panavision Primo lenses).

Let me know what you think, leave a comment below. If you like this article, please consider subscribing. Thank you.